The Complex Problem

Infrastructure is an essential part of modern society; it is the engine that keeps everything going. From roads, bridges, and water systems (water supply, wastewater, and stormwater management) to public services like schools, pools, arenas, libraries, health care facilities, transit, and more, we depend on them every day. However, this critical and aging foundation is under immense strain from decades of deterioration, added pressure from increased population, climate change, and “large public-sector debt” which is “far outpacing infrastructure investment” (Canadian Urban Institute, 2025). Infrastructure improvements or repairs are a major financial challenge for communities trying to address their immediate needs. When vital systems fail, it results in cascading effects that impact budgets, quality of life, public safety, and the environment, reinforcing the need for climate-resilient infrastructure planning.

In 2016, the Government of Canada unveiled the Investing in Canada Plan (IICP). This is a long-term comprehensive infrastructure strategy, committing over $180 billion over the next 12 years. This is a long-term, comprehensive infrastructure strategy designed to address the growing infrastructure deficit and support sustainable asset management nationwide. However, a 2024 report titled “Towards democracy & equitable prosperity” from the University of Toronto’s School of Cities (2024) declared that eight years into the IICP, “Canada’s infrastructure deficit is estimated at a minimum of $150 billion, and up to a trillion dollars”, stating this will “require multi-solving, cross-sectoral investments from both provincial and federal governments” and is “key to bolstering democracy.” The Canadian Urban Institute (2025) echoed this, saying, “Infrastructure may not be the most glamorous topic of conversation, but if we don’t step up our investments, and soon, the risks to our quality of life and democracy will be huge.”

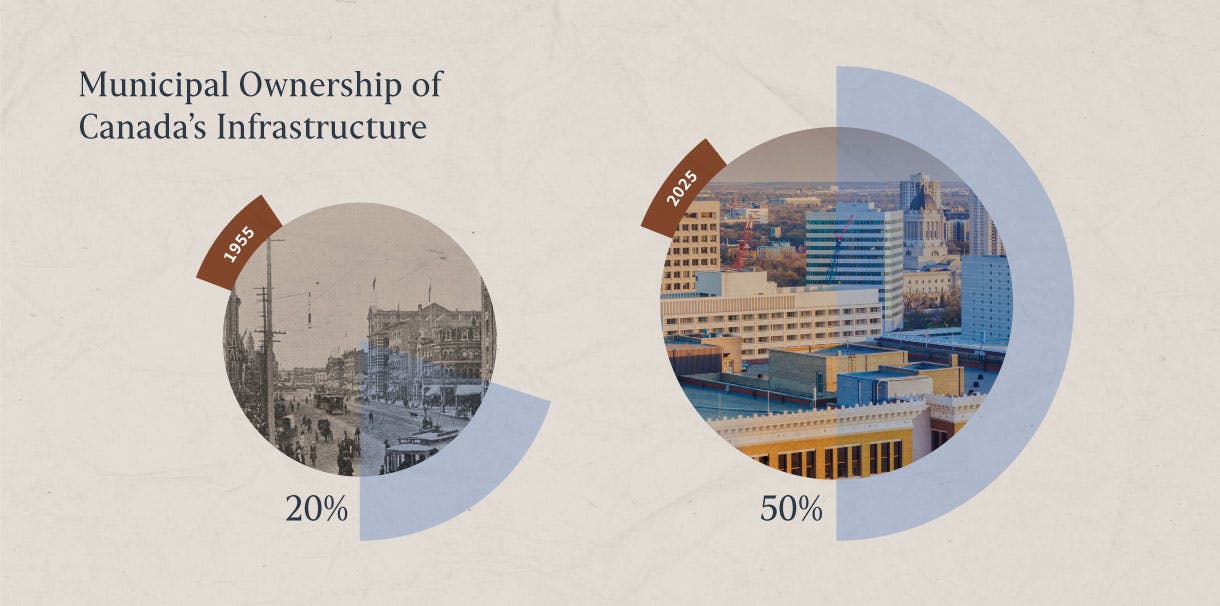

Currently, this financial burden falls disproportionally on municipalities, which must rely primarily on property taxes and the latest round of funding opportunities from provincial and federal governments that have access to broader tax bases. In 1955, “local governments owned just 20% of Canada’s infrastructure”, today that figure is closer to 50%, creating an “unsustainable financial burden” for upkeep, maintenance, and repair (Canadian Urban Institute, 2025). The fiscal reality is that provincial and federal grants are often restrictive, driving municipalities to prioritize projects that align with funding criteria rather than critical local needs and innovation, such as climate adaptation strategies or long-term investments in infrastructure renewal. Canada’s Infrastructure Report Card (2019) brings to light an “urgent need” for these long-term investments in “good, reliable infrastructure [that] supports our quality of life in communities across the country”.

But the question is, how can we achieve this? As communities contemplate important renewal projects or service upgrades, how can we incorporate a strategic, forward-looking investment framework that takes into account the many crises facing us today?

Levelling Up Asset Management

Asset management plans at all levels of government are vital in moving away from a reactive, crisis-oriented management style. However, this technique often prioritizes infrastructure solely by level of deterioration and repair needed. To strengthen asset management further, we need to move away from the “worst-first” model to “highest-risk first.” This can be achieved through a Risk-Based Asset Management approach. It moves beyond the "worst-first" approach to ensure public money targets assets where failure presents the highest overall risk to the city's ability to deliver essential services. While traditional Asset Management Plans focus primarily on cost and performance, a risk-based approach assesses risks as the third component. Below, we have broken down this approach into four steps.

- 1

Asset identification: Creating a catalogue of all municipal assets (roads, bridges, water systems, parks, municipal buildings, etc.).

- 2

Risk Ranking & Prioritization: Determine the likelihood of failure, considering factors like condition and age, as well as the consequences of failure. This includes the social costs of the number of people affected, the risk of pollution, safety hazards, estimated downtime, and emergency repair costs.

- 3

Investment Strategy and Mitigation: Development of a long-term Capital Investment Plan that incorporates prioritization for high-risk assets rather than waiting for failure. This shifts from the “worst-first” model to the “highest-risk first” model. Incorporation of mitigation measures and climate resiliency, where possible, is no longer optional. This includes upgrading materials to withstand climate change impacts such as storm surges. This can also include finding alternatives to current systems, such as alternative energy, as well as enhanced monitoring.

- 4

Review and Revise: The asset management plan is a "living document," updated regularly to incorporate new data, changing climate risks, and evolving citizen expectations.

Municipal asset management should, and is currently, moving away from a reactive, emergency spending model towards a more holistic, proactive approach. Building a long-term municipal Risk-Based Asset Management Plan can support funding applications by demonstrating how a given project aligns with local priorities and meets funding objectives. This can include providing the quantitative rationale for the chosen approach, identifying why the assets are critical in requiring funding for repair and highlighting the implications if the proposed action(s) is ignored.

Additionally, with a long-term outlook, climate adaptation measures can be brought forward and incorporated within repairs or rebuilds to meet future conditions, such as more extreme weather. This helps avoid future capital expenditures by ensuring they can withstand known climate stressors and allow for a more forward-thinking approach that results in benefits beyond post-disaster repair.

Considering Community Benefit

Infrastructure upkeep always comes at a higher cost. While cost-benefit analyses are commonly used within planning, pairing this alongside a Community Benefit Impact Assessment can strengthen the argument for high development costs and display the project’s values beyond financial returns, including societal value and environmental resilience. This community benefit piece can be essential for leveraging certain projects as it examines the non-monetary benefit and consequences of inaction, such as impacts on public health and loss of community access, thereby supporting the justifying of the project’s high upfront investment. This takes the funding rationale approach from a simple return-on-investment calculation to an overall benefit proposition, achieved through the following steps:

- 1

Framework: Developing a structured framework that identifies the effects of a core infrastructure failure and who will be impacted.

- 2

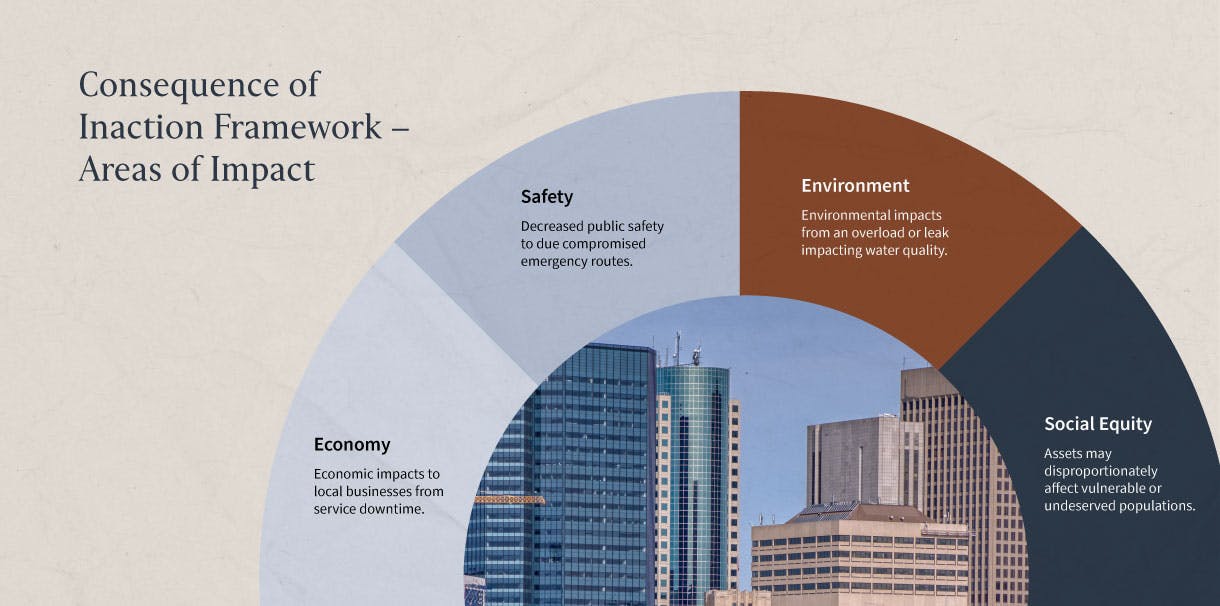

Costs of Failure: Assigning the social cost of service failure through calculating the consequences of inaction by specifically detailing the impacts beyond repair costs, including economic impacts to local businesses from service downtime, decreased public safety due to compromised emergency routes, and environmental impacts from an overload or leak impacting water quality.

- 3

Social & Environmental Justice: Integrating equity and vulnerability data by ensuring the risk ranking process prioritizes assets that disproportionately affect vulnerable or underserved populations when they fail, addressing principles of social justice and supporting environmentally resilient communities.

- 4

Cost Rationale: Providing a cost rationale that justifies high capital expenditures by calculating and breaking down the net positive benefits (economic, social, and environmental) gained from an investment that also reduces future risks and includes resilient design, supporting long-term capital investment planning.

- 5

Confirmation: Incorporating community and stakeholder feedback to verify that the identified non-monetary benefits align with local priorities and needs, fostering public trust in and confidence in the investment.

- 6

Accountability: Community Benefit Agreement.

This, however, leaves us with yet another set of questions. At what point does an infrastructure project demonstrate enough positive social impact and collective community benefit to justify the cost? Using a new street widening project as an example, how can you objectively weigh the environmental impacts against the benefits and desires of the community it would support? While these answers are very location specific based on a community’s constantly evolving needs, desires, and impacts, taking this holistic approach offers a framework to support deliberation to produce an answer.

Holistic Asset Management

Canada has an uphill battle to address an expanding infrastructure deficit while facing down the climate change reality knocking at our door. For municipalities that are responsible for turning provincial and federal mandates and grants into creative solutions for their residents, it can feel like a daunting task and just one problem to solve alongside a long list that includes housing shortages and growing homeless populations.

This challenge will not be simply fixed by finding more money. While additional funding is required, it needs to be met with a shift in management strategies to fundamentally change how we prioritize, value, and plan infrastructure projects. A comprehensive strategy for sustainable asset management shifts us away from reactive short-term spending to a focus on strategic prioritization and holistic evaluation. This is achieved through a dual lens integrating Risk-Based Asset Management alongside a Community Benefit Impact Assessment. The Risk-Based Asset Management’s inclusion of a climate risk assessment ensures climate adaptation and mitigation measures are non-optional, while the Community Benefit Impact Assessment supports and highlights non-monetary returns on investment.

This enables communities to have transparent discussions about what matters most, what benefits are involved beyond the monetary return, and does this outweighs the high project cost. Furthermore, finding a way to demonstrate the reality of this current unsustainable financial burden and the need for flexible funding, allowing communities to be proactive in this transition from a “worst-first” crisis management approach to a proactive and resilient one.

The time for “worst-first” approach is over. We now need to work together with all levels of government to fundamentally redefine the approach to infrastructure and implement this dual framework to prioritize mitigating the biggest risks, leading to proactive investments, build transparency, and ensure climate mitigation is never sidelined.